Martin Ender creates 2D languages of unusual topologies, with code arranged in hexagons, triangles, or using registers arranged in icosohedral structures. We discuss the aesthetics of Funges and golfing languages, and how to both make a complex esolang clear enough for programmers to be able to engage with its central premise.

» First, how did you become interested in esolanging/esoprogramming, golfing, etc? Are you currently in school or working, and if so, as a programmer?

I don't remember how exactly I got there, but I remember reading through various Wikipedia articles on esolangs at some point between 2006 and 2008. The general concept really appealed to me, and while it didn't occur to me back then to try and use one of these languages (let alone design and implement one myself), I had always kept them in the back of my mind.

As for code golf, I used to be very active on Stack Overflow for a while and discovered their code golf community (PPCG) at some point. Initially, I mostly used "normal" programming languages, but the community reintroduced me to esolangs (and introduced me to golfing languages, which I'd consider their own category). Golfing languages ended up being my entry into esoprogramming and the collaboratively designed Marbelous my entry into esolanging.

I suppose my general interest in esolangs stems from the fact that they scratch a similar itch as programming puzzle games (like Manufactoria or games from Zachtronics). Many esolangs are deeply complex emergent systems: I can come up with a few rules to define a language and then spend weeks discovering how programming and golfing works in this model.

I'm currently taking a break between (programming) jobs, which has given me some time to finally finish up Retina 1.0 (which is also somewhere between a practical language and an esolang), design Wumpus and also work on my next esolang.

» In Labyrinth, Hexagony, and Wumpus, you're experimenting with unusual code layouts. Tell me about the appeal of 2D languages, whether funges, golfing languages, etc. What languages were influential for your work and what were you setting out to do differently when you began designing languages in that space -- what ideas are you most interested in exploring?

Back when I first learned about esolangs, Befunge really stood out to me somehow. On one hand, the two-dimensionality is an interesting generalisation of programming languages, and on the other I think I just have a thing for discrete spatial structures (cellular automata and grid structures in general fascinate me to no end). 2D languages are also closest to the above-mentioned programming puzzle games. So it's probably natural that most of my languages gravitate towards this branch of esolangs.

It's interesting that you bring up 2D golfing languages. On one hand, 2D languages are often relatively concise for simpler problems, simply because most of them use 1-character commands by necessity. But I'm only aware of two attempts to create an actual 2D golfing language (Gol><> and Minkolang), both of which tend to result in one-liners when people actually try to golf in them. So either the paradigm is just unsuitable for golfing, or people haven't figured out how to make the extra dimension actually save bytes (which has to make up for the additional bytes that you need to specify the layout).

As for influences, I consider all of my 2D languages fungeoids (maybe Labyrinth less so), so Befunge is clearly a big inspiration, as is ><>. And languages like Fission and Rail have showed me that there's still a lot of room for experimentation in 2D languages.

My usual approach to designing an esolang is that I start from a specific concept or theme and then just roll with it and see what happens. You'll find that most of my esolangs are far from minimal, which is partly because I'm more interested in designing somewhat usable esolangs than Turing tarpits and partly because I often want to see how far I can take the language's concepts. And usually these concepts are things I haven't seen explored in other languages before, or which have been touched upon but which I'd like to investigate more closely.

So for example Labyrinth was just based on the idea that the source code forms a maze, which led to the concept of an instruction pointer (IP) which can determine when it reaches a junction and decides where to move based on a value. That gave me all the control flow I needed, so Labyrinth doesn't have any conditional commands and really relies on this layouting to write nontrivial programs (these days I'm aware that Labyrinth wasn't the first language to explore these ideas — Ropy and Mice in a maze have somewhat similar mechanics). Then I was thinking about whether I could do something novel for source-code manipulation and remembered the board game Labyrinth, where rows and columns of the maze get shifted around.

Hexagony and Wumpus are obviously attempts at exploring new geometries for 2D languages. While browsing through the 2D languages on the esolangs wiki, I was surprised that I couldn't find any languages on non-rectangular grids. Hexagons and triangles seemed like obvious choices to try out and here we are.

Slashes as mirrors or lenses and instruction pointer flow in Alice

And then there's Alice, which started by putting together the observation that the characters / and \ aren't really at 45° angles (which is how most 2D languages interpret them when used as mirrors), and the idea for a 2D language where the direction of movement determines what exactly a command does. The focus on mirrors led to the name Alice, which in turn informed the design choice to have these two "mirror universes" of Cardinal and Ordinal mode, where the two versions of each command are always somehow related. And since I ended up deciding to go for a very feature-rich language here, I also used that opportunity to explore new ideas for control flow in 2D languages (the return-address stack and the iterator queue).

» Hunt the Wumpus seems to have nostalgia value even for programmers long past its era. I noticed the Befunge page on esolangs.org makes special note of the game, saying "Befunge is believed to be the first two-dimensional, ASCII-based, general-purpose (in the sense of 'you could plausibly write Hunt the Wumpus in it') programming language." (with supplied source code for the game). Your language Wumpus builds on the geometry of the game and a geometry similar from other gaming with the icosohedral shape of the register layout, which you describe in terms of a Magic: The Gathering die. First off, what's your feeling about the Hunt the Wumpus game itself? Why do you suggest using the Magic: The Gathering die in particular (as opposed to other 20 sided dice from other systems)? How much is the Wumpus language inspired by gaming, or is it more about an unusual geometry best understood through the prism of such games?

I think it's mostly the latter. The name "Wumpus" definitely came because of the icosahedral data structure and not the other way round (and that Befunge program was a big reason for choosing that name). And I have to admit that I hadn't actually played Hunt the Wumpus myself until I implemented it in Wumpus (although I knew about the game for years).

I really think of Wumpus as Hexagony's counterpart on a triangular grid, so this geometric theme was the driving force behind Wumpus's design.

The icosahedral registers are both a remnant of a planned language that never happened (it was going to be called Triptych, but I ended up splitting it into what would become Wumpus and the language I'm currently working on), and also the desire to avoid having just the usual stack-based memory model of many fungeoids. It's easier to design a new geometry for the code layout and then just use a "normal" memory model and call it a day, but I usually try to have the language's theme inform the memory as well.

I mainly picked the die net from Magic: the Gathering because they're spindown dice, i.e. you can go from face 1 to face 20 by repeatedly tipping the die onto adjacent faces. That seemed like a useful feature to have for a memory model, where you might want use the faces as a small fixed-sized tape for example. It also leads to a nicely symmetrical net when unfolded along this path, which might help reasoning out the various symmetries of the icosahedron (it certainly helped me while designing the language). Of course, you can use any other d20, but then the numbers on the faces might not match up with the face indices used by Wumpus.

So in summary, yes I'd say I picked the references to Hunt the Wumpus and Magic in an effort to make the language more accessible, because people might be familiar with the somewhat mind-bending icosahedral structure from those games.

» Hexagony challenges the linearity of code; even in Befunge, you're executing instructions with one instruction pointer; Hexagony, in using six, forces the programmer to think in multiple code flows, which further complicates the 2D thinking involved. But then you go to great lengths to make the unusual geometries easier to understand, with clear illustrations, and with the great Hexagony colorer that makes the paths of execution easier to understand. First, if you could tell a bit about what inspired the language?

I've already touched upon this above, but as with Wumpus the main inspiration for Hexagony was the goal to bring 2D languages to new geometries (in this case the hexagonal grid). And as I said, I also like the theme to inspire the memory model, which led to weird memory grid (which seems to trip people up more than the hexagonal source code layout).

It's interesting that you think of the multiple IPs as an additional complication. I actually added them more as a convenience. For a start, they're completely optional. I think I added them for similar reasons as the return address stack and iterator queue in Alice: I feel like there's a lot of unexplored territory in 2D languages in terms of control flow, especially when it comes to modularising your code and keeping things organised for more elaborate programs. Hexagony's multiple IPs essentially give you a way to implement a limited amount of subroutines (in fact, they're technically coroutines) without having to worry about grid coordinates. If you have a small task you need to do at various points in your program, you can put it in the source code where one of the other IPs starts and just switch to that IP whenever you want that task executed. Of course, you need to make sure to leave the IP in a position where it can be called again, but still it's often more convenient than repeating the same code multiple times in the program (which might require you to rotate the snippet or even restructure it completely, because Hexagony's control flow isn't rotationally invariant).

Lastly, regarding diagrams and illustrations, you're right that I'm trying hard to make these often weird languages more accessible and I believe that visualisations help a great deal, especially when it comes to geometry. In fact, I wish I had more tools like HexagonyColorer or the EsotericIDE's visual debugger for my other languages (ideally working directly in your browser). Judging by the popularity of games from Zachtronics and the like (even though it's clearly a niche), I'm sure there are a lot of people out there who would actually enjoy playing around with these kinds of languages but who might be put off by the abstractness or by all the stuff they have to keep in their head while using the languages. Having accessible and shiny tools for exploring the languages could go a long way towards getting more people interested in esolangs.

Despite the name, I didn't design Hexagony to be painful to program in (nor any of my other languages), but I also don't like to compromise the integrity of the language's theme by falling back onto more familiar programming concepts. So I also always consider how to make the language more accessible, and additional features beyond the Turing-completeness of the language as well as detailed and illustrated language specifications are two big parts of that. Visual and interactive tools will be the third part that I hope to get around to some day.

» Tell me more about golfing languages: how do these languages take different approaches to solving the same problem? The challenge for golfing languages to allow programmers to be concise is almost the opposite of the minimalism of, say, brainfuck, where the language is tiny but the programs huge. How do you design a language toward these ends, and are there different general approaches?

You're right, designing golfing languages is quite different from designing esolangs. While these languages are still far from production languages, they share with those that they are designed to solve a problem (in this case, expressing a variety of programs in as few bytes of code as possible). These languages normally don't try to be quirky, they just sometimes end up being quirky because everything the language can do without you explicitly saying so (but meaning to) is great.

Of course, part of making a concise language is providing a large number of built-ins, which can solve useful tasks or subtasks in a single byte. So in order to maximise the number of built-ins you can provide, modern golfing languages make use of all 256 byte values. To that end, they usually define their own code page, so that all of those bytes are printable and, if possible, represent characters that provide somewhat reasonable mnemonics.

But it seems to be a bit of a misconception among less experienced golfing language designers that just throwing together a bunch of built-ins is all it takes to create a great golfing language: it's generally not very helpful to have a "FizzBuzz" built-in, because while that lets you solve this particular problem in a single byte, it also wastes that byte for another useful command (because it's probably not going to be used in any other program). So for a start, you'd rather want to think about a good set of built-ins that combine easily to build lots of different short programs.

But even then, built-ins are only part of the language's design and probably even the less important part: the real meat of designing a golfing language is coming up with language semantics and syntax that avoid redundancy. It's especially important to avoid the need for parentheses or other characters which are only there to specify the order of operations. Ideally, you'll just want to be able to put the operators you need into the source code in some order that just makes things work, without having to specify every single operand explicitly. And this is where golfing languages have taken several very interesting (and I'd say roughly equally successful) approaches.

GolfScript, and by extension CJam, started a tradition of using stack-based semantics to avoid the need for referring to operands. And even the very popular (and successful) 05AB1E is stack-based. But stack-based languages still sometimes have the problem that you end up wasting several bytes on reordering the stack so that your arguments are in the correct order (unfortunately, I don't know 05AB1E well enough to tell whether or how it solves this problem, but it's certainly a very competitive language).

Jelly instead takes inspiration from J and defines how various combinations of nilads, monads and dyads are composed into useful functions which are applied to the inputs (similar to J's hooks and forks). Interestingly, there's a layer on top of that which lets you combine the built-in functions into others using higher-order operators which is stack-based (i.e. the parser keeps track of a stack of functions which you can combine with those operators).

And then there's Husk, which is a pure functional and strongly typed language like Haskell. Here, the strong typing is used to infer the order of operations automatically so that each function in the resulting expression tree gets a valid list of arguments.

There are other approaches out there, both explored and unexplored, but the competition and exposure these languages have received on PPCG has already led to some very impressive and varied language design (e.g. there's also Brachylog which is a declarative golfing language based on Prolog). The first generation or two of golfing languages don't normally stand a chance against any of these modern ones.

» Some of your languages are concise in their menu of commands (Hexagony) while others, like Alice, have lengthy lists, compared to many esolangs. What is your thinking in deciding what to offer, and how friendly to make a language, apart from getting its programmers to think in the topographical space and program flow rules you've constructed?

I actually often have a hard time deciding on this when designing a language. With Labyrinth and Hexagony, I just decided not to use any letters to keep the number of commands reasonable but then filled up all the characters I had. It just seemed inelegant to have a few random letters in there, because then I really would have wondered "Why these commands and no others? Where do I stop?". (The only exception is v, because it goes so well with <>^.)

For Stack Cats I was much more restricted from the start: due to the symmetry constraints which are the core of the language, I only had a limited set of characters to work with, and it was already decided which of these would be involutions and which would be mutual inverses. There aren't a whole lot of characters to work with here, and I wanted most of them to act as mnemonics, but in the end I ran out of good ideas for interesting involutions first, so I didn't even use all of the characters available.

For Alice, I made a conscious decision to go for a feature-rich 2D language (because I was already overloading them with the two different modes; why would you start overloading if you still have characters left to assign). So Alice uses all printable ASCII characters as commands. That ended up being quite a challenge, because at some point coming up with interesting new ideas for commands starts to get tricky, but I'm quite happy with the final set I ended up with. The large number of commands let me explore some fun ideas that would have been scrapped in a more concise language, and I've already found use even for a lot of the more obscure commands.

The good part about the language's design is that I could get away with some really wonky commands if they neatly corresponded to a reasonable command in the other mode. For example there's a command which lets you replace the divisors of a number, but that's completely fine because one of the language's themes is that it associates characters with prime factors and substrings with divisors. So this weird built-in is the counterpart of a fairly standard substring replacement.

Wumpus was the first time I had the confidence to pick a set of commands based on what seemed useful and thematic instead of forcing myself to fill up some predefined set of characters. While choosing commands I looked at ways of manipulating the various language concepts I provided (the stack, the grid and the icosahedron) in natural ways and designed the operators around that.

» You mention "Many esolangs are deeply complex emergent systems: I can come up with a few rules to define a language and then spend weeks discovering how programming and golfing works in this model." Could you tell us about esolangs in particular that you've had this experience with?

The first language that comes to mind is also my first esolang Labyrinth. For example, as I said, I added the grid rotation commands simply based on the boardgame Labyrinth, but without any real use case in mind. I also started out designing the language with the (in my opinion) very consistent rules of how the instruction pointer behaves at each possible junction depending on the value on top of the stack. I was left with a single case where there wasn't a natural choice where to go (paths to the left and right, but the top of the stack is zero) and decided to make this choice random, which seemed like a neat way to get randomness into the language without having to provide a specific command for it.

Now, it turns out that it's impossible for the IP to end up in this specific configuration unless you make use of the grid rotation commands. That's something I never intended but the two independent mechanics of the language ended up meshing quite neatly. Grid rotation also turns out to be quite useful for golfing and for writing busy beavers, but I feel like I haven't even scratched the surface of what's possible with these commands.

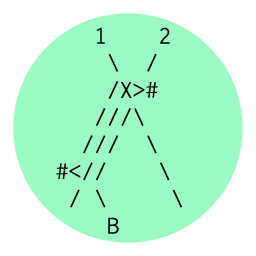

With Alice, for example, I found out some time after completing the language that it provides an idiom I wish some production languages had. Consider a case where you want to run a loop for a while but you want to alternate between two different pieces of code for each loop iteration (so even iterations do something else than odd iterations). This can be useful, e.g. to process both a list and the separators between list elements in one go. Alice's jump commands sort of separate the IP's position from its direction (the return address stack remember the position but not the direction), which lets you implement this kind of loop very neatly:

...number of iterations...&w...even iteration...v

. k

>...odd iteration...k>...end of loop...

The k jumps back to the w, and by turning the IP around before jumping back we can make sure that we alternate between the two different loop bodies.

There's also Stack Cats, where I still haven't figured out how to write concise programs effectively which make use of both halves of the code. I found a construction that lets me skip the first half of the code and only executes the second half, which circumvents the language's symmetry restrictions. All non-trivial programs I've written (including "Hello World" and a prime number test) make use of this construction, because I still don't know how to make use of both halves. But I've started writing programs that search for short programs to simple tasks and it's fascinating to see the techniques these programs use (and it also turns out that such a search can be sped up significantly by applying considerations from group theory to the program space, because Stack Cats programs do form a group).

» What other topological spaces or structures are interesting to you, in terms of code or otherwise, or that you might want to explore in other languages?

I have quite a backlog of language design ideas. I'm usually not very comfortable speaking about those until they're done, but I'll try to mention a few.

The language I'm currently working on actually has fractal topology, but that makes it sound a lot worse than it is. The fractal nature is mostly related to the fact that the language is functional and provides something akin to infinite, lazy lists and how the language handles recursion without providing named functions. The source code itself also doesn't really resemble a fractal. It's more about the language's structure.

I'm also quite fascinated by aperiodic tilings, and I'd like to make a 2D language work on one of those. I've had this idea for a long time, but I wanted to get Wumpus done first. With that out of the way, I might actually tackle this sooner than later.

Knot theory is also very interesting, and it might be fun to design a language around it where the source code is an ASCII representation of one or several knots. Looking at the esolangs wiki, I don't seem to be the first person to come up with this idea, but so far no one seems to have actually designed such a language (I'd have to learn a lot about knot theory before I do though).

There are other ideas I'd like to explore for 2D languages as well, without even going crazy on the topology. For example, I'd like to see what happens when the instruction pointer of a 2D language covers more than one grid cell at a time. Or a language based on the mechanics of match-3-type puzzle games. Or a declarative 2D language (there's a severe shortage of declarative esolangs from what I've seen).

And then there's a whole bunch of ideas that aren't even 2D at all, like a language based on juggling (particularly the Siteswap notation used for juggling patterns). The backlog is quite long, and I seem to be better at growing it than shortening it.