Scott Feeney, a.k.a. Graue founded esolangs.org, the central resource for esolang knowledge. In this interview, he explains esolangs as puzzles and makes a case for the esoprogrammers as underrated heroes of esolanging.

» How did you first connect with the esolang community? What was it like at the time?

It was around 2005. The esolang community was mostly centered on the #esoteric channel on Freenode, as it is now, but there was also a mailing list on sange.fi — already declining in usage and a bit spam-filled, but still occasionally used. There wasn’t a great central resource for info on esolangs, and we had this perennial problem of information disappearing. Someone would post up a page about a cool language, attract attention, then their site would go down and it would be lost. The closest to a central resource was the Catseye site, but that kept moving and at one point was offline for months or more.

That motivated me to start a wiki and a file archive, both of which I hosted for years. The wiki was public domain, and sanitized database dumps (without user information) were made available daily, with instructions on how to create automatic backups. The file archive was in Subversion (for these were the days before Git, or at least before Git was mainstream), and you could check it out, update it and have a backup as well. All of this was intended to protect the info in case I disappeared into the woods and stopped paying my hosting bill, though in practice, none of the backups stuck around as all of *those* people slowly walked away.

» Have you spent much time programming in other esolangs? Is that something you did more early on, or continued to do once you were designing your own languages?

I spent a bit of time writing Brainfuck programs, but found it difficult and frustrating. Which is kind of the point, right? I wasn’t a very mature programmer at the time, and it seemed hard to figure out a memory layout and control structure that would allow my programs to work. It was much more fun (and, in retrospect, less interesting) writing my own Brainfuck *implementations*.

There’s a reason there are more esoteric languages and implementations than there are programs written in them, by a wide margin. People like the novelty, but get spooked when they face real difficulty; it certainly happened to me.

» Are there esoprograms in particular that stand out to you? What makes something a great esoprogram?

So, I think what’s most interesting about esolangs is the conversation between languages, which ask questions, and programs written in those languages, which answer the questions. When you build a new esoteric language with a weird set of constraints, you get people thinking: I wonder if I can do X in this language? I wonder if there’s a way to do Y? And figuring that out, by writing programs that do X and Y, can be a fun challenge.

One shortcut we take is to talk about computational classes. If you prove that a language is Turing-complete, then it can do any computation a “real” language can do, albeit awkwardly and inefficiently. And Turing-completeness says nothing about input and output. You might have to come up with a translation layer, where you encode your input into the memory cells of your esolang interpreter, then run the program, and when the program terminates, decode the memory cells to get the output. Having done that, though, you can write any program you want in PROLAN/M, the Collatz function, or Bitwise Cyclic Tag, all of which *look* even less like usable programming languages than Brainfuck.

Qdeql is one of the questions I posed: it’s an esolang I came up with in 2005. Whereas Brainfuck is based on a one-dimensional array of memory, and many esolangs use a stack, Qdeql was based on a queue. After playing around with it a little bit, I got frustrated, and basically said, “Well fuck, you can’t do anything with this language. I fucked it up.” And I tried again, writing [Sceql](http://esolangs.org/wiki/Sceql), thinking I would do it right this time, and that Qdeql had been a dead-end.

I also added a solid explanation to Esowiki of why Qdeql wasn’t usable for computation:

To be able to access arbitrary amounts of data in a Qdeql program would require storing that data in the stack. But accessing any particular byte more than once requires knowing how many bytes are in the stack, and to determine this would require accessing a particular byte more than once. Therefore, it is not possible to access arbitrary amounts of data in a Qdeql program.

This puts Qdeql into a situation similar to SMETANA’s [a Chris Pressey language], where the amount of memory a program can use is limited by the size of the program.

Years later in 2012, and purely as a matter of bookkeeping, I decided to tag the language as a finite-state automaton, which my reasoning implied.

Little did I know Ørjan Johansen would take that as a challenge. Several weeks later, he made an edit with the summary “I find your conclusion … premature.” He went on to fill out the Qdeql page with details of an incredibly sophisticated construction that lets you overcome the problem I described and translate a Brainfuck variant into Qdeql! Ørjan’s key observation:

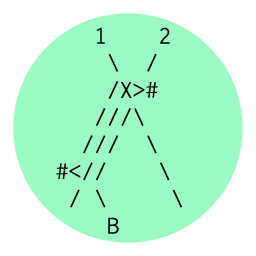

The code \/\// will skip over (dequeueing and re-enqueueing) an arbitrary length string of nonzero 0 0 triples terminated by a 0, with the mild inconvenience that the terminating 0 at the end will be deleted.

I love this whole exchange. It sums up to me why something as obscure and seemingly useless as esoteric programming languages holds interest. I built a set of shackles I thought no one could escape from. And much, much, later, Ørjan did this whole Houdini act and broke out of it.

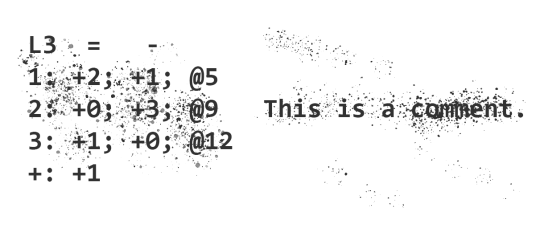

It inspired me to take a second look at another 2005 language of mine, Sortle. Sortle was designed to have an execution model unlike any language I knew of. You defined a bunch of named expressions, and they were sorted and run “in order”, except that each expression then renamed itself to whatever it evaluated to, and the list was re-sorted, and you could only store data in the expression names. A bunch of people had looked at Sortle and been like “hmm, interesting language”, and no one seemed to have any idea what its computational class was.

So in 2012, in response to Ørjan, I tried to prove Sortle Turing-complete, and did so by implementing Bitwise Cyclic Tag in it. This felt like cheating. Bitwise Cyclic Tag is so minimal, it seems like I did nothing at all. But that’s how Turing-completeness works. Just take the dumbest possible Turing-complete thing, write an interpreter for it in your new esolang (or compile it to your new esolang), and you’re done. I also wrote a digital root calculator in Sortle, inspired by Daniel B Cristofani’s digital root calculator in Brainfuck, and finally after a full day’s work, I came up with a Sortle quine. That quine is my favorite program that I personally have written in an esolang.

» Tell me about the process of developing a language. The thought process is very different working in different languages (in C vs. SQL, let alone Befunge)… is that point of view of the language something you consider early on when designing a language, or does it evolve as you build it?

It has been almost a decade since I designed an esolang. I think my thought process was usually, “How can I make a language whose computational model is based on $CONCEPT?” (insertion sort -> Sortle, queues -> Qdeql) or “How can I make an even more minimal and restricted version of $ESOLANG?” (2L -> 1L_a).

I think one problem the Esolang community faces is that there’s a constant influx of people who don’t understand the challenge/response nature that makes esolangs interesting. People think Brainfuck is funny because it has “fuck” in its name, and decide to make a language that’s entirely swear words, and each swear word gets mapped to a different Brainfuck instruction. Stuff like that. Well, that isn’t really interesting. There’s no question to answer. Is it Turing complete? Duh, you can convert any Brainfuck program to it using find and replace. And these kinds of languages aren’t interesting to the people who make them, either, because these people don’t stick around. They just litter the Esowiki with more and more of them, and it makes it hard to find the languages that are actually asking questions and posing challenges. We don’t have a process for removing or filtering out the junk, the unfunny joke languages.

I wish reading the Esowiki felt more like you were being presented with a set of obscure, yet fascinating problems you can try to solve.

» Does Bitwise Cyclic Tag exist pretty much just to prove other languages’ Turing Completeness?

I guess that sounds about right. Honestly, I just believed it was Turing-complete because the wiki said so. I see now that the proof lay on a page on GeoCities, no longer available, so I’m not exactly standing on solid ground here claiming I proved Sortle Turing-complete. Goes to show esolangers are hobbyists, not researchers, especially me.

» Sortle reminds me a bit of Malbolge and other languages with self-modifying code, in that evaluating a command affects how (or in this case when) that command is next executed in the code itself. Were there any languages in particular you looked at while working on Sortle? Could you describe the “string-rewriting paradigm”?

The string rewriting paradigm means that you have strings — ordered sequences of characters, text basically — as your data structure, and your program consists of rules for turning strings into other strings. And by repeatedly running these rules, you compute something.

I may have been influenced by PROLAN/M, though I’m not sure about timing. Thue and Muriel are obvious examples of string-rewriting languages that predate Sortle and that I may or may not have been thinking about.

But I was definitely familiar with SMETANA before writing Sortle. SMETANA, while not based around strings at all, shares the element of program steps affecting the execution order.

So does Forte, which I discovered later. Forte is one of my favorite esolangs. You have to read the examples on the esowiki. They’re a trip. I’ve told people about Forte in non-esoteric programming discussions, using it as an example of why mutable collections are unnatural and [immutable collections](https://github.com/facebook/immutable-js#the-case-for-immutability) are good. Forte is a language where even numbers are mutable objects, and it’s ridiculous.

» Did writing the brainfuck implementations help you when you started constructing your own languages? Do you usually write a compiler or interpreter, and how do you go about doing this (or how would you, if you were doing it now)?

Writing a Brainfuck interpreter definitely made it easier to implement Sceql and Qdeql, which are very similar languages. The only part I found even moderately challenging about implementing these three languages as an amateur programmer was getting the jumps right, matching the appropriate [ with the appropriate ] in Brainfuck, and likewise for \ and / in Sceql and Qdeql. The syntax for these languages is incredibly simple. Tokenizing is trivial (each token is one byte).

Sortle was a different beast. I had to parse multi-character words and strings, allocating memory manually for each one, since I chose to write in C, my main language at the time. In doing so I managed to confuse myself totally. The original C interpreter only executes some trivial Sortle programs correctly. Regexes are seriously broken. I had to write a new interpreter years later before I could explore the language’s possibilities.

I usually wrote interpreters, and probably would now, too. Might start by writing some test programs and expected output if I did it today. Serious programming has shown me the value of testing.

» It’s interesting that a number of esolangers I’ve talked to describe themselves as having been hobbyists, or “not mature programmers” at the time they were writing esolangs. Is creating a language technically complex?

Drawing up the spec is pretty easy, if the language doesn’t need to be useful or solve real-world problems. Implementing it, that depends. Languages that are more imperative and procedural in nature are simpler to implement, I find, than languages based around rewriting paradigms or functional programming. Hev, for example, was apparently challenging for Chris Pressey to implement: https://github.com/catseye/Hev/blob/master/src/Hev.hs#L177-178 Likewise, languages that have fewer constructions in their syntax are less trouble to parse, as I mentioned before.

» It seems like the community is pretty welcoming, in terms of not overly policing the wiki (you’ve mentioned the proliferation of poor brainfuck clones which is perhaps a side-effect of this), and in the curiosity given to new languages. I myself have posted some not-so-well-thought-out languages and had people engage with the them and make interesting suggestions. Do you think this this generosity is due to the core community still being relatively small? How much of the discussion these days is centered on the wiki vs. other forums (proggit etc)? Any interesting stories from your time there that you’d like to mention? Any other languages you’d like to mention that ask interesting questions?

I don’t think I have much to add. I already told you the languages I like :) and my engagement with the community these days is, sadly, minimal.

But you’re right, this community is a pretty friendly and approachable one. Can’t say for sure why that is. Perhaps because it takes a healthy curiosity, open-mindedness, and even a sense of humor, to be interested in esoteric languages at all. Also, generosity comes easier when so little is at stake. We know we’re not going to get famous or build the next big startup through playing with this stuff. If we thought we were, then well, there’d be a little more to disagree about, wouldn’t there?