Code is built on other code, which we can describe in terms of layers, both internally to the language and in terms of how the code interacts with other systems: with high-level languages (Java, C#, etc) sitting above assemblers, machine code, etc, down to the hardware itself. This layering adds simplification, an abstracting away of details that might be distracting or unnecessary. Most of the time, when you copy a string from one place to another, you don’t want to be tied up in what’s happening at the register level.

However, those details at the bottom can cause strange behaviors when they’re not considered. As Friedrich Kittler puts it in his essay “There is No Software”:

the so-called philosophy of the so-called computing community places all its stock in hiding hardware behind software, and electronic signifiers behind human/machine interfaces.

and:

The higher and more effortless programming languages have become, the more unbridgeable the gap grows between them and the hardware that still does all the work.

Joel Spolsky, in his Joel on Software blog mentions this gap, lamenting that many programmers trained only in high-level languages (such as Java) often don’t fully understand the mechanics of what’s happening below. This can lead to algorithms that scale poorly or to make poor decisions in how memory is handled. As he puts it in another post:

What is a string library? It’s a way to pretend that computers can manipulate strings just as easily as they can manipulate numbers. What is a file system? It’s a way to pretend that a hard drive isn’t really a bunch of spinning magnetic platters that can store bits at certain locations, but rather a hierarchical system of folders-within-folders containing individual files that in turn consist of one or more strings of bytes.

Spolsky describes these algorithms as “leaky,” meaning they fail to describe the behavior – the next level down, contradictory metaphors might in play. He uses the example of the communication protocol TCP/IP, where TCP is dependable, yet is built entirely on the undependable IP. For Spolsky, “all non-trivial abstractions, to some degree, are leaky,” like the datastore that slows down when a seemingly arbitrary threshhold is reached, or the SQL query that takes orders of magnitude longer to run when a redundant clause is removed, invoking a different execution plan.

For Kittler, this layering and hiding has a political dimension as well, at least when we get all the way down to the chip itself. Kittler’s “Protected Mode” essay looks at restrictions on chip access, which, beginning with their 386, had Intel relegating all “untrusted code” (i.e. all the code we write) to a level of access where we can no longer decide for ourselves how it executes at the chip level. For Kittler, this is done with no technical basis in mind, but solely for the benefit of Intel and Microsoft’s corporate concerns; we can never truly have full control of the machines we own or write code for.

* * *

The Checkout language proposal (the language itself not yet implemented) by ais523 tries to bring back this control, without forcing programmers to write a whole program in machine code. With each command, the programmer specifies the level where it should be executed. This means the coder can drill down all the way to the chip level when needed, but blocks of code at that level can be run through flow control in a higher, more abstract layer.

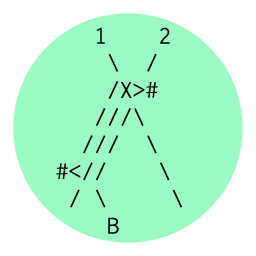

Checkout has six levels: any command must have its level specified. Level 1, the lowest, corresponds to a single thread, while level 6 is the equivalent of an entire computer system. Level 1 is used mostly for arithmetic and has limited access to memory; level 3 is used for memory management, and level 2 for low-level commands like MOV. When a programmer wants more robust control over program flow, there is level 4:

Level 4 contains Checkout’s major control flow structure, parloop/4, which creates a number of level 3 subunits that execute in parallel, each of which contains a number of level 2 subunits that execute in parallel, each of which contains a number of level 1 subunits that execute in parallel.

So the programs are built from the bottom up. Level 5 has larger memory stores, and then level 6 brings back in control structures necessary to make Checkout a Turing Complete language.

To get around the modern equivalent of Protected Mode, Checkout runs on the GPU (the graphics processor), which has fewer restrictions, and can run faster than a CPU (if Checkout is implemented with that chip in mind). Ais523 claims that a Checkout program could potentially run even faster than machine code, which often is not modeled on current chip design.

Checkout is named for its checkout command, which hands off control of memory from one level to another (“checkout/5” moves or copies data between level 5 memory and level 6 memory, etc). The nop instruction (no-op, for “no-operation”) pauses execution in order to keep various threads in sync (there’s a nop/1, a nop/2, etc). The particular flavor of each hierarchical level is described in detail on the esolang.org page, from memory allocation to parallelization to how execution is interleaved through the hierarchical structure.

Many esolangs are low level, created out of a desire to experiment with code closer to the machine, behind the optimizations and memory protection of languages like Java and C#. Checkout uses malloc and free, the memory allocation tools associated with C, which run at its top levels (5 and 6). Even the outermost level of Checkout is conceptually closer to the machine than Java. Although high level languages may offer some lower level access (through compiler hints or “unsafe code” allowing pointer arithmetic, etc). Checkout puts these decisions in the forefront, not only allowing the programmer to control the process down to the chip level, but forcing her to think in terms of this hierarchy for the entirety of the program.